I like Gog.com. Not only does it have a massive library of old games available in DRM-free packages which will play nicely with modern machines (even, generally, those running Linux); but their sales often remind me about games I haven’t played in years – generally going for super-cheap prices too. So, for the ridiculous price of £0.87, I couldn’t pass up having another go at Deus Ex: Invisible War, a title that almost killed Deus Ex as a series but which I actually remember more fondly than the original.

First appearing on the PC in the year 2000, the original Deus Ex was an ambitious title mixing elements of stealth, action and role playing games into a a conspiracy-enthused cyberpunk thriller. A thriller which – remarkably – offered the player a degree of freedom to control the narrative. It was very highly regarded at the time. In his review of the sequel in 2004, Eurogamer’s Rob Fahey described it as being ” widely regarded as a defining moment for PC games and was indeed one of the first (and only) games that we ever awarded a 10/10 score on this site.”

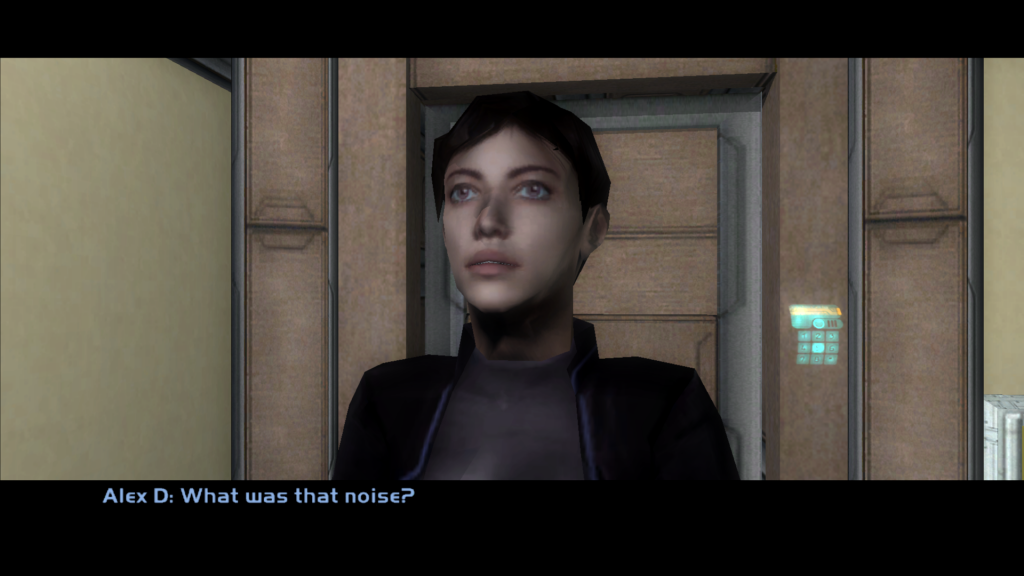

Appearing in 2004, Invisible War was a direct sequel picking up the story twenty years later with a fresh character, Alex D. For the most part the game plays similarly to the original. Controlling Alex from a first person perspective, the game tasks the player with completing missions from a number of competing shadowy organisations, slowly uncovering elements of a deep conspiracy that ceaselessly leads Alex towards an epic climatic show-down and one final all important choice.

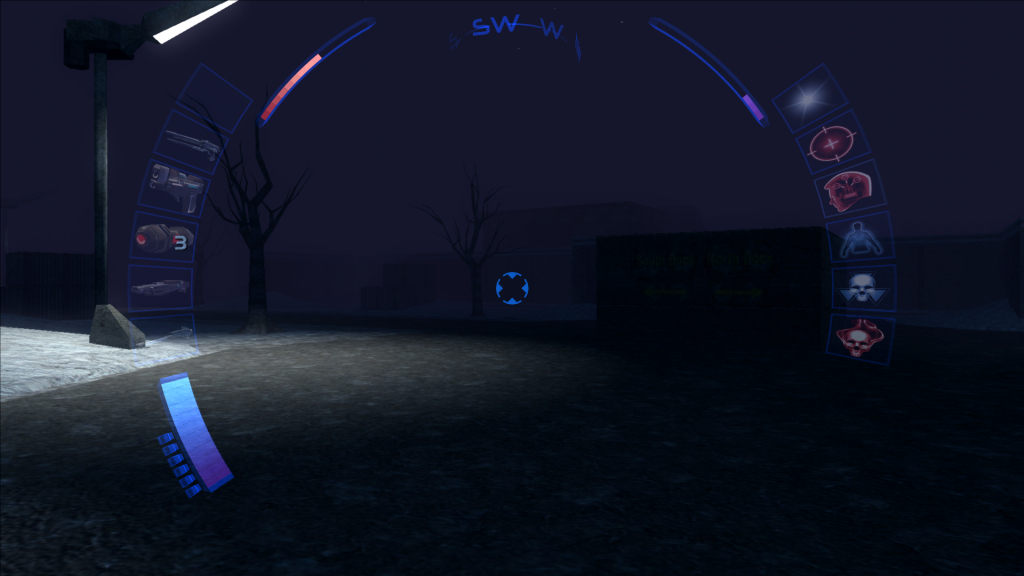

The game’s overriding theme is freedom and choice, which plays out through a couple of mechanics: The objectives set for the player by the various organisations are regularly conflicting (say, rescuing or executing the same person) which effectively forces the player into backing one side or another. With genetic alteration also being another main theme, the game also allows you to alter Alex’s abilities via biomod canisters, which can either be unlocked by completing some missions or looted from the environment. Biomod super powers generally come in one of three flavours: skills that will help Alex sneak past bad guys, skills that will allow Alex to hack computers and turn the enemies defences against them or skills that turn Alex into a one-person army.

Returning to it after twenty years myself, I realized that my memories of both titles weren’t terribly strong. Playing through the original via the slightly-compromised PlayStation 2 port (A number of large areas had to be trimmed to fit into side the PS2’s smaller memory footprint ), my overall impression at the end was one of disappointment: The player’s decisions have a minimum impact on the narrative of the original, with the last section effectively allowing you to nullify every choice you’ve made throughout the rest of the game.

My impressions of the second were much more favourable, however. Part of this was quite possibly the fact the £0.87 I paid the other day was £0.87 more than I played for the game originally. Back in the early 2000s, UK retailer Special Reserve used to run a review competition which allowed the winner to choose a free game. I wouldn’t say I was the world’s greatest writer (this retrospective is probably evidence of that), but as a uni student I had a clear advantage over other people writing I when it came to structuring and communicating my thoughts. Consequently, For a couple of years I managed to build up a pretty impressive library of original Xbox games while keeping my student loan completely intact. It’s a complete mystery why Special Reserve eventually went out of business.

Beyond the price, I think i was impressed because Invisible War does a better job of delivering on the promise of freedom than the original game. Admittedly, you are still irresistibly drawn towards a final showdown, so most of the impact of your choices is restricted to dialogue changes, but there are still plenty of choices to be made throughout the game, with some not even acting as formal objectives. You can grass on criminal behaviour you’ve seen to the nosey, government-connected NG Resonance chat bot, for example, but are the extra credits worth being a pawn in shady government surveillance? You can even choose Alex’s sex at the beginning of the game and the decision has a knock-on effect on the way some of the characters interact with you. The world feels – to a very limited extent today – alive.

It’s hard to believe today, but something else that was incredible about Invisible War were the graphics. The level geometry probably isn’t the best on the Xbox, but the lighting and shadows make the world feel incredibly dynamic On top of that the faces on the in-game characters also felt surprisingly human. Chuck in some bump mapping (a very exciting thing around the turn of the millennium), and you had a very impressive looking game on your hands.

On top of that, the worlds are also surprisingly interactive. It’s very satisfying that, when the player encounters locked doors and chests, grenades and explosive mines generally make for satisfyingly useful lock picks. If there’s a vent shaft entrance that’s out of reach, the player can simply pick up and place an object to allow them to climb up to it. The amount of freedom the player has to solve each particular challenge make for a very open, dynamic experience.

Given the game’s negative reputation, there are definitely some problems present. One is the story. At a micro level, the writing and voice acting are better than you’d probably expect from a game of this era, the script seems to keep up well with some of the more erratic choices the game allows you to make. I opted to torch a guy’s business, interrogate him at his flat but then saved saved his daughter from a grisly fate and the dialogue went from anger to a sort of reserved gratitude in a way which didn’t draw me out of the experience.

Other elements of the writing, however, didn’t work so well. Looking back at development, Ion Storm lead Warren Spector lamented listening to a focus group that wanted the next Deux Ex moved into the further future and – bizarrely – for the characters to wear purple jump suits. Designer Harvey Smith, meanwhile, thought they had written the wrong renderer and the wrong AI, but was especially critical of the story:

Aside from condemning original lead JC Denton to a bit part and undermining the Cyber Punk asthetic, some of the macro story elements definitely don’t gel very well. Invisible war contains, for example, the world’s worst Illuminati: having kept themselves hidden for the first half of the game – not to mention the countless centuries before – they spend the second half telling anyone who’ll listen that they are, in fact, the illuminati. You’d think the first rule of Illuminati club would be to not tell anyone you were a member of Illuminati club.

Another issue the team obviously had was not knowing how far they should simplify the interface for console gamers. Though this simplification has some benefits – both inventory and biomod screens are simplified without any major less of function – there are some strange decisions in there too. Though notably praised by Eurogamer at the time, by far the worst decision was forcing all of the games firearms use the same type of ammo – be they pistol, flamethrower or rocket launcher. Though admittedly this does cut down on the user having to juggle clips, shells and rockets, more combative players will find this limits the effectiveness of the games more powerful weapons. Yes, they might have much greater stopping power, but in return they burn through your ammo very very quickly.

A final issue is a bit of a more complex one. Objectively, I would say it amounts to a problem. Subjectively I would say, it’s arguably the entire reason you should consider giving Invisible War a today. You see, up until the early noughties, PC first-person shooters and console first-person shooters were fundamentally different beasts. Yes, one might get ported to the other (We’ve already talked about PS2 version of the original Deus Ex while the likes of Halo etc made it to the PC), but all of these ports suffered from being after-the-fact truncation or expansions of the original. You could tell they weren’t really intended for the platform they were currently being played on.

Invisible War should be taken as a totem of a new breed of first person games. Developers (or, more precisely, publishers) were realising that the ever-growing console market was where the real money was, and they should really be making sure that all of their first-person games were being developed with both PC and console markets in mind from the beginning. Luckily for Ion Storm they were able to restrict Invisible War’s console release to the original Xbox (the most powerful machine on the market at the time), but this was still less than ideal: with just 64mb of RAM, the Xbox only just about hit the minimum spec needed to run the PC version of the original Deus Ex.

When firing the game up for the first time, the compromise Ion Storm reached in order to produce something which improved on the original game while remaining achievable on the Xbox becomes instantly obvious. The environments are small. Very small. Early on, you’ll most likely visit a night club which acts as the perfect example of the size environment Deus Ex 2 can fit into in a single load: it gives you an office, a medium sized dance floor, a couple of rooms above and a conveniently-navigable ventilation shaft, this isn’t a very big area at all.

The limited scope can definitely be considered as having a negative effect on some areas of the game. Take the biomods, for example. In the original game, JC Denton can install a leg modification that allows him to bound around Hell’s Kitchen, leaping from the floor to the roofs in a single bound. Such a modification simply isn’t available to Alex, and the most probable reason is that they simply don’t need it. Even when walking around the city ‘hub’ worlds, the locations are restricted to a hand full of shops, a couple of alley ways and an apartment building or two…and most of the shops are small enough to avoid the need for a cat-swinging biomod as well.

With such small individual locations, larger area are split across several loads, which means you’ll spend a lot of time looking at loading screens. It’s less of an issue now you can shove your games onto super-fast SSD storage, but having them read from a DVD at the speed of the original Xbox’s drive is painful to say the least. There can be no denying that, if you were designing a game from scratch, you wouldn’t include the kind of compromises found in Invisible War on purpose.

Weirdly, however, that might also be its key strength. If almost all other action video games seek to be a 70s Bond film, with dramatic showdowns taking place in grandiose locations, the artfully anticlimactic nature of most of Invisible War’s missions feel more like one of Fleming’s original short stories: you sneak in, pick a lock (or blast your way in and shoot a couple of people), complete your mission, get out. Playing through it again with twenty years hindsight its a really interesting one. Though its mechanics and atmosphere were clearly born of the teething problems of merging the worlds of PC and console FPS together, I’d say I’ve not played another game quite like that allows you to quickly and efficiently complete missions that feel like they’re making a genuine difference to an AI character’s world. Ok, yes: it is a sequel and it does owe most of its ideas to the original Deus Ex. However, as an experience it feels very much its own thing, and its something I haven’t felt like I’ve experiences before or since.

Though financially successful – It sold more copies than the original at least – Ion Storm proved unable to continue the series. None of the endings left room for a fully engaging sequel to take place after Invisible War, while the twenty year ‘collapse’ between the Deus Ex games didn’t lend itself to an engaging environment for a new game. With Invisible war, they’d accidentally poisoned the well. Plans for a Deus Ex 3 started, but none came to fruition save for a plan for an action-based spin off that eventually turned into Project Snowblind. Though Deus Ex eventually returned in 2011 courtesy of Eidos Montreal, it notably abandoned the world of Invisible War, rewinding the clock to a time before the original Deus Ex. Overall then, Invisible War can be considered as both an interesting artifact in its own right and the game which almost destroyed the Deus Ex franchise. For the price of £0.87 who could say no to that?