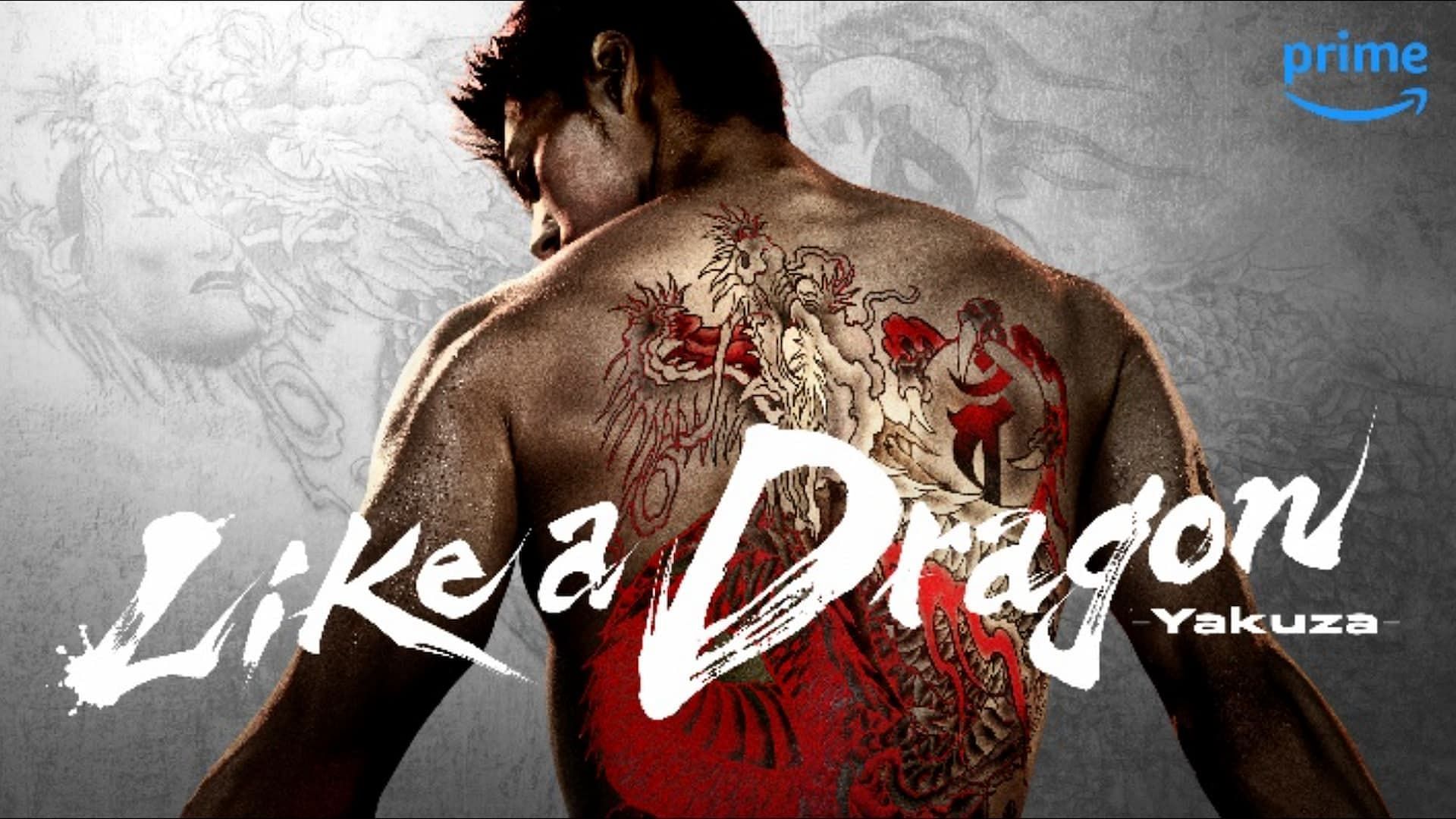

Could Sega’s legendary Gangster series really work as a TV adaption?

So, after being teased for about four years, the TV series based on Sega’s Like a Dragon/Yakuza series has finally been unleashed onto what seems to be a mostly indifferent public. Coming hot on the heels of Amazon’s well-recieved Fall Out adaption, Weirdly even the global giant themselves seem to have put very little effort into marketing it – or even pushing it in the video app itself.

Regardless of Amazon’s questionable marketing choices, anyone who can track it down in the Prime Video interface might very well be in for a treat. For fans of the original games, the central pillar of the story will be instantly familiar: The year is 2005 and Kazuma Kiryu has just been released from prison only to find his former clan is in disarray. 10 billion has vanished from their bank account, and unless it’s returned quickly a lot of people are going to end up getting hurt. Though exiled from the Yakuza, it quickly becomes obvious that he and his former companions are caught up in the mess, and it will be up to Kiryu to identify the culprits and return the money.

This series isn’t about fan service, and though the central tenent of the story is the same the differences start to mount quickly. Most obviously, the story unfolds via a dual narrative As Kiryu and Yumi unpick what’s happened in 2005, the audience regularly hops back in to 1995 in order have events in the future contextualised via snippets of an all-new backstory which breaks completely from the events of prequel game Yakuza 0 and finds Kiryu and chums fall in with the Yakuza after pulling off a heist at an arcade they fail to realise is run by the brutal Dojima family.

I’m not going to go into too much detail as I want to keep the review as spoiler free as possible, but I think there’s plenty to like in the series. From the opening titles through to the end credits, the whole thing has a premium feel too it, and has plenty of gorgeous shots that bring Kamurochō to life. Though Ryoma Takeuchi was cruelly dismissed as ‘Kid-yu’ based on early promotional shots, he and Kento Kaku (Nishki) do a good job of bringing gravitas to their roles, creating distinct past and future versions of their characters. I’d also say lot of the story changes aren’t necessarily bad either. Let’s not forget that when Team RGG remade the original Yakuza for modern consoles in 2016 they made a number of changes themselves, adding in extra story scenes to explain how the care free Nishki they’d created for their own prequel ended up as the the embittered (and slightly under cooked) enemy found in the original 2005 Yakuza.

With that said, a number of changes do present issues. Though it’s nice to have Yuumi Kawai’s Yumi as a central character in both arks, Aunt Yumi’s presence means that TV Kiryu never has to grapple with guardianship and parenthood in the way he does in the game, meaning one of the main themes of the character and the series itself is absent. This change also renders Haruka as a motivational object – she doesn’t have the screen time needed to develop into the driven, independent character she is in the game.

In fact, I’d say when the changes create problems they’re generally linked to one common issue: time.

We can view this one mathematically: A speed run (i.e. no extras, a player starting from the beginning and getting to the end as quickly as possible, watching none of the story) of the original PlayStation 2 Yakuza can be done in as little as 120 minutes. That’s skipping the entire story, however: A player soaking in the narrative will probably take at least 600 minutes to do so. The original Yakuza only covers the 2005 potion of the show as well. Throw in prequel Yakuza 0 as well and you’re looking at at least 1000 minutes of content. Even if you halve that to compensate for time spent fighting and running around the city in the game, we can say the makers of the series had to compress around 500 minutes worth of story stuff into a 240 minute run time.

Part of this is achieved by slimming the narrative, subtlety getting from A to D without needing to visit B, and C. This works to an extent: If you have no prior Yakuza experience it won’t exactly feel like like you’re watching a story with chunks gouged out of it and it definitely keeps each episode feeling tight. However, even when is isn’t essential to the narrative, you’re missing on the stuff that makes Yakuza so brilliant as a series, the parts that add an extra dimension to an otherwise uninteresting character, or ask difficult questions about the nature of Japanese society.

An obvious example of this is the Florist of Sai, who employs Kamurochō homeless’s in his vast underground intelligence network. In the game Kiryu abandons his main line of enquiry to help an issue a problem the Florist is having with his son. Though we are informed of his hatred of Yakuza (and his personal history with Detective Date) the episode shows his pragmatism as a person, while his entire ‘purgatory’ asks difficult questions about what happens to people who fall on hard times. Though we see a glimpse of both the Florist and his central lair, the pruning of the side story means that all the interesting tension that rounded the character is gone.

It’s not just peripheral characters who are affected by this lack of time either. Though Munetaka Aoki firmly understands the assignment of playing long-term series favourite Goro Majima, he simply lacks the screen time to explore the character’s full mixture of wackiness, honour and brutality. The same is true of Suaru Shibutani’s Detective Date who – Aside from some convenient early exposition at the prison gates – doesn’t really fit in with the altered story at all. In fact, both characters’ presence feel kind of like the kind of smug, brainless fan service the show seems to be consciously avoiding. I may feel better about some of the more negative changes if the new plot offered something substantive in their stead, but some of the new narrative ideas aren’t exactly earth shattering: A fighter having to choose between the personal glory of winning and helping his family by taking a dive is a plot device I’m sure most of us will be familial with.

So is it a bit of a disaster? Have the TV show creators done a bad job? After all, the Yakuza games contain the kind of narrative stories that should be made for this. The equally linear Last of Us adapted beautifully to TV, so why wouldn’t the core Yakuza story work just as well?

In fact, if we strip back twenty years of continuous improvement and go back to the original PlayStation 2 game, we find most of the usual arguments you could make against adapting Yakuza are theoretically blunted. For a start, there’s a lot less to do: playable arcade games didn’t show until the sequel, so Kiryu only has a couple of gambling games and a claw machine and some err…adult entertainment… to keep himself busy with. On top of that, the side stories are a lot less wacky than the ones the series has become known for: finding lost items, helping people being threatened by Yakuza, acts of kindness towards the homeless…in the original Yakuza that’s more or less all you get. On the surface it should be a prime candidate for adaption.

Yet if we accept the wackiness as an optional extra, I’m not entirely sure that anything that isn’t a video game would truly feel like a Yakuza title. Playing without all of the fun extras added to the later titles, I think the underlying formula works because of three prongs. Obviously, you have the stories which combine moments of tender humanity with a harsh political cynicism. Then you have the side stuff and the mini-games that add a bit of extra interst. Finally – and this is an important aspect which actually gets in the way of the game play of the original PS2 games – you have the locations themselves. Though the camera was improved to be less disorientating in later entries, in the original title Kamurochō is viewed through sweeping street scenes which often leave Kiryu as quite literally a small part of the bigger picture. The streets are teeming with life and – as he passes – the game shows snippets of the conversations (or is it the inner voices? It’s not made quite clear…) of the people around him. In an era where Rockstar’s Vice City felt more like a theme park constructed for the player’s amusement, Kamurochō is a living, breathing city that the player just happened to be assisting Kiryu to exist in.

Put all together, the Yakuza games work because, as a medium they do things film and television can not. With a great plot and well-acted roles, we can feel sympathy for members of the Tojo Clan in a TV adaption and will them to succeed over the Omni Alliance. However the limits of medium mean we’re inevitably focusing on characters rather than the places. We might want Kamurochō to be saved as part of our heroes’ wider goals, but we have no deeper attachment to it than that.

When playing the game, however, we’re constantly switching between active participants and casual voyeurs. The switching of head space is useful because switching to one refreshes you from the other. If the game was just an endless array of goons to pummel with bicycles and traffic cones, the initial rush would wear off pretty quickly and the game would probably be quite boring. The cut-scenes on their own, meanwhile, are often long and intense. If you were to try and make a TV show by just daisy chaining them together with a couple of fight scenes I think the overall product would be mentally fatiguing and wouldn’t necessarily be a fun watch.

On top of that, Kamurochō is physical place we explore and become connected to in a similar manner top a real physical space: We have our favourite place to pop in and buy restoration items and we quickly learn our optimum routes from one side of the town to the other. After spending hours interacting in the environment we have a greater connection than we ever could with a TV show. When the plot leads to somewhere being blown up in a TV show, the characters hurt. When it happens in the game, we hurt a little bit too.

Consequently I think Yakuza represents arguably the perfect symbiosis of story and gameplay in an interactive context. Where something like The Last of Us feels like a film with some interactive bits tacked on; the story, combat engine and the wider world of Yakuza fuse together as one surprisingly cohesive whole, which each of the individual elements acting as the perfect balance for another. The Yakuza series doesn’t succeed in spite of being a video game, the series works BECAUSE it’s a video game. This is what makes it a difficult adaption.

Returning to the TV show then, I think we need to bare this in mind. The central joke in the 2005 film Tristam Shandy was that the novel the characters are trying to turn into a movie is fundamentally unfilmable, and I think we have to view Like a Dragon: Yakuza, in a similar light. Given they had to squeeze an experience that was ten hours long and arguably unfilmabble into six forty minute episodes, they did a good job. Aside from more Majima – I think an intense, tightly-based high-pace mob thriller is about the best anyone could really have achieved. It’s definitely watchable, though whether you want to spend time with a compromised product in a world where the practically perfect originals exist is pretty much up to you.