So the other day we learned that the lovely people behind Pokémon (Nintendo and Gamefreak) would finally be coming for Pocketpair, developers of the suspiciously-similar-looking Palworld. Though this didn’t exactly come as a shock to anyone, many were surprised that Nintendo choose to target Pocketpair for patent infringement, rather than for copying the iconic Pokemon characters. In reality this probably isn’t quite as surprising as it seems. To find out why, lets take a look at a patent case that might have seen Sonic the Hedgehog appear on Atari’s Jaguar.

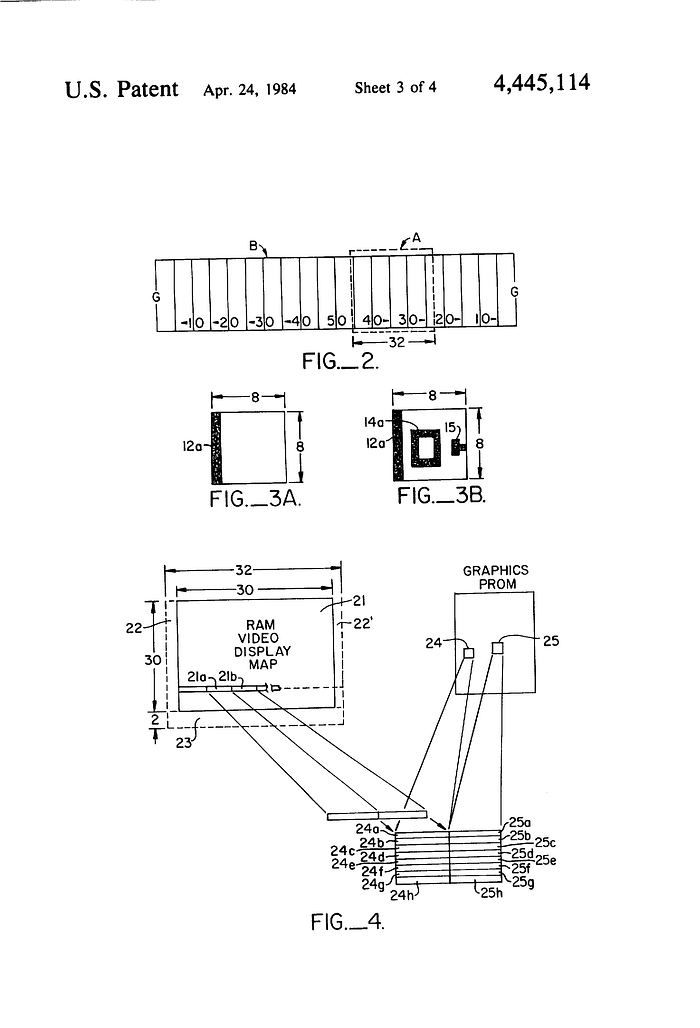

The story begins in 1980. By that point, Atari had spent most of the previous decade pioneering arcade video games and had invented a lot of the basic techniques that were fundamental to the art of making video games. As the originators, they were in a prime position to patent a lot of these principal inventions so it probably shouldn’t come as a surprise that in 1980 we find Atari designer David Stubben submitting US patent US4445114A, which covers a method of creating a scrolling image in a video game. According to its abstract:

A video game includes apparatus for scrolling playfield objects appearing on the display unit of the game. The apparatus selectively offsets the address used to access an addressable random access memory containing data indicative of the TV picture displayed. The random access data, when accessed, is used to address a video data memory which provides the building block components of the video display. Further scrolling effect is obtained by selectively delaying the video data communicated to the video display unit.

If this sounds suspiciously like Atari were patenting something as simple as delaying when data is written to the VRAM, well that’s because that’s exactly what they were doing. This is one of the reasons why patents are often both highly controversial and a good way for a company to shutdown competition: though in the outside world we wouldn’t allow the inventor of the aeroplane to kill the helicopter by patenting a concept as broad as powered flight, in the realm of computers we find that the patent system has often allowed companies to protect areas which are almost as broad.

Of course what happened next in the industry is well known: Though Atari were riding the crest of a wave in 1980, both the US arcade and home video game markets collapsed in 1983. Atari never really recovered. Though they had a successor to their hugely successful VCS (and less successfull 5200) ready to go in 1984, its release was postponed by the decision of Atari owners Warner to split the individual Atari divisions and sell them off.

Bought by Commodore founder Jack Tramiel, the old Atari console and computer divisions — now named the Atari Corporation — couldn’t catch a break. Their fancy new 16-bit computer ( the Atari ST) struggled against the Amiga (a machine designed by members of the original Atari computer division working for Tramiel’s former company) and while the 7800 did eventually see a release in 1986, it struggled to carve a niche against superior machines from Sega and a massively-dominant Nintendo. In 1993, Atari attempted to leap-frog the entire 16-bit console generation with the Jaguar — a console they claimed was the world’s first 64-bit machine — but even with this bold and somewhat misleading marketing they were unable to find the sizable audience they needed.

Fortunately for Atari, by the mid 1990s you didn’t actually need to sell consoles and games to make money from the industry. When we think of the traditional ‘console wars’ we think of gladiatorial advertisement campaigns, angry correspondents printed in video game magazine letters pages and endless tech spec comparisons. However, the most brutal fights of all would arguably take place in American court rooms, with companies fighting to either preserve a part of their business or aggressively shutdown their opposition.

Don’t believe me? Nintendo sued Atari Games (the spun-off arcade wing of the original Atari) for reverse engineering the technology used to restrict the NES to official Nintendo licensees. Sega — who had been a long-time critic of Nintendo’s licensing practices — about-faced and sued Accolade for reverse- engineering the dastardly protection mechanism Sega themselves had built into their Megadrive. While all this was going on an inventor named Jan R. Coyle came out of the woodwork to sue just about everyone — Sega, Atari, SNK, Atari — for infringing a patent he filed for displaying images on a TV screen in the mid 70s. The videogame industry was definitely keeping the courts busy.

Given the general atmosphere of legislative tomfoolery, it probably isn’t too surprising to find out that Atari Corporation — who had inherited a lot of precious patents from the original Atari — launched their own legal cases. They had cause, to be fair: not only were the licensing practices engaged in by first Nintendo and then Sega questionable under antitrust laws, but scrolling screens had gone from being notable in 1980 to a basic feature of almost every action game. This made it likely that both Nintendo and Sega had infringed patent US4445114A with their own games at some point. Atari started proceedings against Nintendo in 1989 and told Sega they intended to sue the following year.

When it came to Nintendo, Atari failed to make its anti-trust accusations stick in court. While the jury decided that Nintendo had a monopoly-like power, they couldn’t decide if a monopoly had been Nintendo’s intent. 1–0 to Nintendo. However when it came to defending themselves against US4445114A, Nintendo weren’t anywhere near as lucky. Interestingly, rather than dispute Atari’s claims about infringing the patent, Nintendo’s defense was to try and invalidate the patent itself. This wasn’t such a bad strategy: for a patent to be valid, it has to be an original invention that hasn’t been publicly disclosed. This rule makes sense — allowing retrospective patent filing after competitors had used publicly-available technology in good faith would be a patent troll’s dream.

Unfortunately for Atari, Nintendo found what was potentially a dangerous chink in their armour — and amusingly it was one of their own games. Created by the arcade wing in 1977, ‘Super Bug’ was an impressively visionary game that allowed players to drive a Volkswagen Beetle around a free-scrolling (but mostly empty) road-scape. Though Atari had included it as a reference material when filing US4445114A, they’d never actually got around to finishing the patent application for Super Bug itself. Nintendo consequently argued that the Super Bug game and its manual constituted a prior art. If the court agreed, patent US4445114A would have been invalidated and Atari wouldn’t have had a case. Nintendo requested the patent be reexamined, but unfortunately for them, Atari were able to successfully argue that US4445114A’s ‘secret sauce’ was the delay mechanism that sat between the data being read from the ROM and fed into RAM. This mechanism isn’t obvious from the game itself nor is it mentioned in the manual, meaning that neither met the threshold needed to count as prior art. A second reexamination was requested, but the patent held up so Nintendo had no choice but to settle and pay Atari a substantial royalty. Ouch.

It had taken three years for Atari to get their case against Nintendo into court — from 1989 to 1992 — but with Sega it took even longer. The two first started doomed settlement negotiations in 1990, tried again in 1993 and the case finally reached court in 1994. Once again, Atari had trouble getting antitrust accusations to stick. This time, they sort a rather worrying injunction that would have prevented Sega from selling their consoles and software until the case was concluded. This injunction request was beaten down in brutal fashion: Not only was Atari’s claim of irreparable harm questioned by the court (it had taken them three years to formally file a suit against Sega after all), but Sega also introduced a host of retail witnesses — Alan Fine from Kay Bee Toys, Jeffrey Griffiths from Electronics Boutique, Daniel Dematteo of Software, Inc. and John Sullivan of Toys R Us — who all testified that Sega were irrelevant to the question of them carrying Atari stock. Atari was a company with a reputation for over promising and then under delivering to retailers — if Sega vanished overnight, the retailers argued, they would simply carry more Nintendo stock. Ouch again.

So far so good for Sega then, but there was still the question of US4445114A. With Nintendo having confirmed the patents validity, Sega opted to question whether their games were really infringing. To do this they had a very useful ally: in July 1990 Sega employed the (now former) Atari engineer David Stubben to assess whether Sega’s current crop of games really were infringing on the patent he himself had created. It was shaping up to be quite the legal battle.

Except, in September 1994, it was suddenly announced that Sega and Atari had reached a settlement. Why? There maybe a couple of explanations. For one, the legal dice had not been rolling in Sega’s favour lately. Not only had their courtroom victory against Accolade been overturned by (what would become) a highly important appeal verdict, but they were also the only company who had decided to challenge the patent cases brought by Jan R. Coyle — ironically covering his idea of a ‘Sonic Coloring System.’ This had been a costly mistake: Initially ordered to pay the inventor $33 million in April 1992, this had risen to a final settlement of $43 million by May. Blimey. It’s definitely understandable that, in light of this, Sega may not have wanted to gamble with another — potentially larger — multi-million dollar judgement.

The substantial sum paid to Coyle might have already dissuaded Sega of America against another speculative court room defense, but, there’s also evidence that hints that Sega’s case may not be quite as strong as it seems. In November 1993, Sega and Atari had met to discuss a settlement to the case, and Sega’s counsel had voluntarily given a tape of an interview with David Stubben to Atari’s legal team. Sega’s team had been lax in doing this: it seems at no time did they make it clear that the tape was intended for those settlement negotiations exclusively, and wasn’t to be used by Atari in court. In the event, Atari not only intended to use the interview as evidence but asked the court to issue a subpoena for documents around its creation. Unfortunately we don’t have access to the tape today, but we can say that while Sega seem to have been initially fine for Atari to include the tape in their discovery, they were later very keen to both shoot down Atari’s subpoena AND to limit the scope of Stubben’s testimony in court.

Whether Sega were spooked into settling by their previous legal setbacks or were left with their case undermined by some of the evidence around the Stubben tape, we can say the settlement deal they reached with Atari was quite comprehensive. In return for licensing 70 of Atari’s patents and for dropping all claims against each other, Sega agreed to pay Atari $50 million. and to buy a further $40 million of Atari stock. Iif that deal wasn’t sweet enough the settlement was also a co-licensing deal between the publishers: Sega and Atari agreed to license up to five titles a year from each other’s libraries from 1995 up to 2001.

From documents archived by the good folks at SMS Power! We can see that Atari were very serious about this: by the 30th of November 1994 Atari had already procured a list of potential titles from Sega, by the 2nd of December they’d already picked the ones they were most interested in and by the 7th they’d already had a reply from Sega about games they believed to be ‘accidentally’ missing from the list.

So what of our deliciously click-baity title then? Could we have actually have seen Sonic title on the Atari Jaguar? It turns out the answer is no. Though they’d been backed into a corner, Sega managed to be canny about what was included in this deal. As we can see from both the list and the reply from Sega’s Anne S Jordan, propriety characters like Ecco the Dolphin and Sonic the Hedgehog were off the table. From an interview with Sam Tramiel in Ultimate Gamer, we also learn that the games had to be at least a year old before the other party could use them and — presumably because the original Atari arcade wing had been spun off as a separate company — coin-op releases from both sides were off the table as well.

In fact, in the interview Sam Tramiel argues that AtSo the other day we learned that the lovely people behind Pokémon (Nintendo and Gamefreak) would finally be coming for Pocketpair, developers of the suspiciously-similar-looking Palworld. Though this didn’t exactly come as a shock to anyone, many were surprised that Nintendo choose to target Pocketpair for patent infringement, rather than for copying the iconic Pokemon characters. In reality this probably isn’t quite as surprising as it seems. To find out why, lets take a look at a patent case that might have seen Sonic the Hedgehog appear on Atari’s Jaguar.

The story begins in 1980. By that point, Atari had spent most of the previous decade pioneering arcade video games and had invented a lot of the basic techniques that were fundamental to the art of making video games. As the originators, they were in a prime position to patent a lot of these principal inventions so it probably shouldn’t come as a surprise that in 1980 we find Atari designer David Stubben submitting US patent US4445114A, which covers a method of creating a scrolling image in a video game. According to its abstract:

A video game includes apparatus for scrolling playfield objects appearing on the display unit of the game. The apparatus selectively offsets the address used to access an addressable random access memory containing data indicative of the TV picture displayed. The random access data, when accessed, is used to address a video data memory which provides the building block components of the video display. Further scrolling effect is obtained by selectively delaying the video data communicated to the video display unit.

If this sounds suspiciously like Atari were patenting something as simple as delaying when data is written to the VRAM, well that’s because that’s exactly what they were doing. This is one of the reasons why patents are often both highly controversial and a good way for a company to shutdown competition: though in the outside world we wouldn’t allow the inventor of the aeroplane to kill the helicopter by patenting a concept as broad as powered flight, in the realm of computers we find that the patent system has often allowed companies to protect areas which are almost as broad.

An illustration from US4445114A

Of course what happened next in the industry is well known: Though Atari were riding the crest of a wave in 1980, both the US arcade and home video game markets collapsed in 1983. Atari never really recovered. Though they had a successor to their hugely successful VCS (and less successfull 5200) ready to go in 1984, its release was postponed by the decision of Atari owners Warner to split the individual Atari divisions and sell them off.

Bought by Commodore founder Jack Tramiel, the old Atari console and computer divisions — now named the Atari Corporation — couldn’t catch a break. Their fancy new 16-bit computer ( the Atari ST) struggled against the Amiga (a machine designed by members of the original Atari computer division working for Tramiel’s former company) and while the 7800 did eventually see a release in 1986, it struggled to carve a niche against superior machines from Sega and a massively-dominant Nintendo. In 1993, Atari attempted to leap-frog the entire 16-bit console generation with the Jaguar — a console they claimed was the world’s first 64-bit machine — but even with this bold and somewhat misleading marketing they were unable to find the sizable audience they needed.

Fortunately for Atari, by the mid 1990s you didn’t actually need to sell consoles and games to make money from the industry. When we think of the traditional ‘console wars’ we think of gladiatorial advertisement campaigns, angry correspondents printed in video game magazine letters pages and endless tech spec comparisons. However, the most brutal fights of all would arguably take place in American court rooms, with companies fighting to either preserve a part of their business or aggressively shutdown their opposition.

Don’t believe me? Nintendo sued Atari Games (the spun-off arcade wing of the original Atari) for reverse engineering the technology used to restrict the NES to official Nintendo licensees. Sega — who had been a long-time critic of Nintendo’s licensing practices — about-faced and sued Accolade for reverse- engineering the dastardly protection mechanism Sega themselves had built into their Megadrive. While all this was going on an inventor named Jan R. Coyle came out of the woodwork to sue just about everyone — Sega, Atari, SNK, Atari — for infringing a patent he filed for displaying images on a TV screen in the mid 70s. The videogame industry was definitely keeping the courts busy.

Given the general atmosphere of legislative tomfoolery, it probably isn’t too surprising to find out that Atari Corporation — who had inherited a lot of precious patents from the original Atari — launched their own legal cases. They had cause, to be fair: not only were the licensing practices engaged in by first Nintendo and then Sega questionable under antitrust laws, but scrolling screens had gone from being notable in 1980 to a basic feature of almost every action game. This made it likely that both Nintendo and Sega had infringed patent US4445114A with their own games at some point. Atari started proceedings against Nintendo in 1989 and told Sega they intended to sue the following year.

When it came to Nintendo, Atari failed to make its anti-trust accusations stick in court. While the jury decided that Nintendo had a monopoly-like power, they couldn’t decide if a monopoly had been Nintendo’s intent. 1–0 to Nintendo. However when it came to defending themselves against US4445114A, Nintendo weren’t anywhere near as lucky. Interestingly, rather than dispute Atari’s claims about infringing the patent, Nintendo’s defense was to try and invalidate the patent itself. This wasn’t such a bad strategy: for a patent to be valid, it has to be an original invention that hasn’t been publicly disclosed. This rule makes sense — allowing retrospective patent filing after competitors had used publicly-available technology in good faith would be a patent troll’s dream.

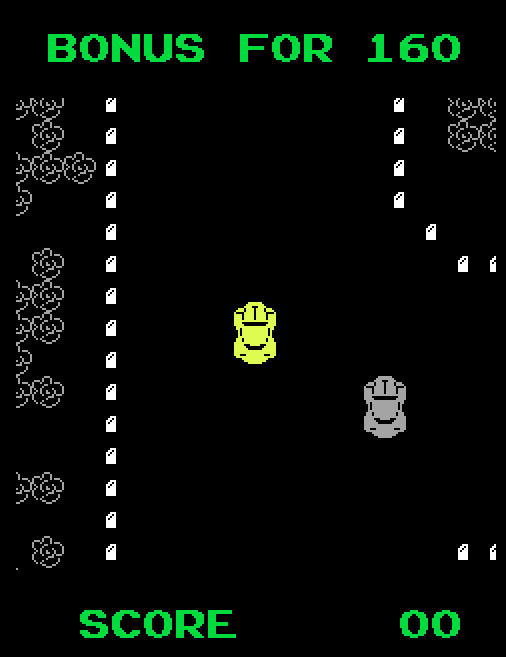

Unfortunately for Atari, Nintendo found what was potentially a dangerous chink in their armour — and amusingly it was one of their own games. Created by the arcade wing in 1977, ‘Super Bug’ was an impressively visionary game that allowed players to drive a Volkswagen Beetle around a free-scrolling (but mostly empty) road-scape. Though Atari had included it as a reference material when filing US4445114A, they’d never actually got around to finishing the patent application for Super Bug itself. Nintendo consequently argued that the Super Bug game and its manual constituted a prior art. If the court agreed, patent US4445114A would have been invalidated and Atari wouldn’t have had a case. Nintendo requested the patent be reexamined, but unfortunately for them, Atari were able to successfully argue that US4445114A’s ‘secret sauce’ was the delay mechanism that sat between the data being read from the ROM and fed into RAM. This mechanism isn’t obvious from the game itself nor is it mentioned in the manual, meaning that neither met the threshold needed to count as prior art. A second reexamination was requested, but the patent held up so Nintendo had no choice but to settle and pay Atari a substantial royalty. Ouch.

Atari’s Superbug (which wasn’t a stark warning about antibiotic resistance, surprisingly)

It had taken three years for Atari to get their case against Nintendo into court — from 1989 to 1992 — but with Sega it took even longer. The two first started doomed settlement negotiations in 1990, tried again in 1993 and the case finally reached court in 1994. Once again, Atari had trouble getting antitrust accusations to stick. This time, they sort a rather worrying injunction that would have prevented Sega from selling their consoles and software until the case was concluded. This injunction request was beaten down in brutal fashion: Not only was Atari’s claim of irreparable harm questioned by the court (it had taken them three years to formally file a suit against Sega after all), but Sega also introduced a host of retail witnesses — Alan Fine from Kay Bee Toys, Jeffrey Griffiths from Electronics Boutique, Daniel Dematteo of Software, Inc. and John Sullivan of Toys R Us — who all testified that Sega were irrelevant to the question of them carrying Atari stock. Atari was a company with a reputation for over promising and then under delivering to retailers — if Sega vanished overnight, the retailers argued, they would simply carry more Nintendo stock. Ouch again.

So far so good for Sega then, but there was still the question of US4445114A. With Nintendo having confirmed the patents validity, Sega opted to question whether their games were really infringing. To do this they had a very useful ally: in July 1990 Sega employed the (now former) Atari engineer David Stubben to assess whether Sega’s current crop of games really were infringing on the patent he himself had created. It was shaping up to be quite the legal battle.

Except, in September 1994, it was suddenly announced that Sega and Atari had reached a settlement. Why? There maybe a couple of explanations. For one, the legal dice had not been rolling in Sega’s favour lately. Not only had their courtroom victory against Accolade been overturned by (what would become) a highly important appeal verdict, but they were also the only company who had decided to challenge the patent cases brought by Jan R. Coyle — ironically covering his idea of a ‘Sonic Coloring System.’ This had been a costly mistake: Initially ordered to pay the inventor $33 million in April 1992, this had risen to a final settlement of $43 million by May. Blimey. It’s definitely understandable that, in light of this, Sega may not have wanted to gamble with another — potentially larger — multi-million dollar judgement.

The substantial sum paid to Coyle might have already dissuaded Sega of America against another speculative court room defense, but, there’s also evidence that hints that Sega’s case may not be quite as strong as it seems. In November 1993, Sega and Atari had met to discuss a settlement to the case, and Sega’s counsel had voluntarily given a tape of an interview with David Stubben to Atari’s legal team. Sega’s team had been lax in doing this: it seems at no time did they make it clear that the tape was intended for those settlement negotiations exclusively, and wasn’t to be used by Atari in court. In the event, Atari not only intended to use the interview as evidence but asked the court to issue a subpoena for documents around its creation. Unfortunately we don’t have access to the tape today, but we can say that while Sega seem to have been initially fine for Atari to include the tape in their discovery, they were later very keen to both shoot down Atari’s subpoena AND to limit the scope of Stubben’s testimony in court.

Whether Sega were spooked into settling by their previous legal setbacks or were left with their case undermined by some of the evidence around the Stubben tape, we can say the settlement deal they reached with Atari was quite comprehensive. In return for licensing 70 of Atari’s patents and for dropping all claims against each other, Sega agreed to pay Atari $50 million. and to buy a further $40 million of Atari stock. Iif that deal wasn’t sweet enough the settlement was also a co-licensing deal between the publishers: Sega and Atari agreed to license up to five titles a year from each other’s libraries from 1995 up to 2001.

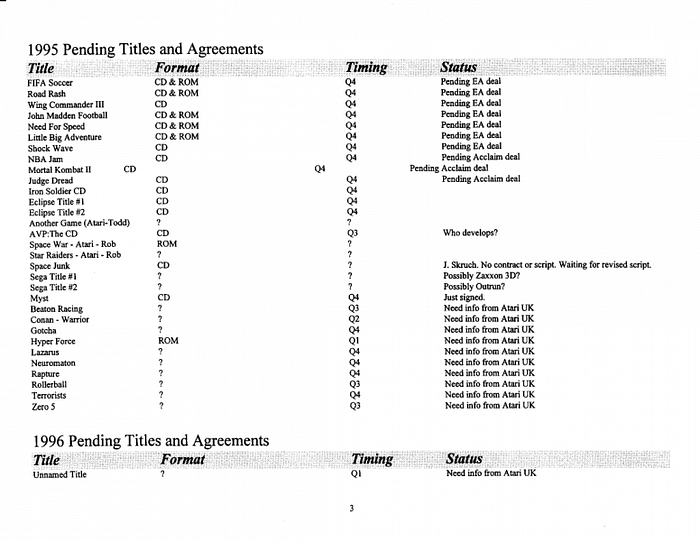

From documents archived by the good folks at SMS Power! We can see that Atari were very serious about this: by the 30th of November 1994 Atari had already procured a list of potential titles from Sega, by the 2nd of December they’d already picked the ones they were most interested in and by the 7th they’d already had a reply from Sega about games they believed to be ‘accidentally’ missing from the list.

So what of our deliciously click-baity title then? Could we have actually have seen Sonic title on the Atari Jaguar? It turns out the answer is no. Though they’d been backed into a corner, Sega managed to be canny about what was included in this deal. As we can see from both the list and the reply from Sega’s Anne S Jordan, propriety characters like Ecco the Dolphin and Sonic the Hedgehog were off the table. From an interview with Sam Tramiel in Ultimate Gamer, we also learn that the games had to be at least a year old before the other party could use them and — presumably because the original Atari arcade wing had been spun off as a separate company — coin-op releases from both sides were off the table as well.

In fact, in the interview Sam Tramiel argues that Atari’s library was more useful to Sega than Sega’s was for them. He might have actually had a point: aside from Atari’s legacy of classic arcade games (well, the ancient home ports of them at least), the early release of the Jaguar console meant that Sega would have had access to Jaguar titles like Tempest 2000 and Cybermorph before Atari had access to the tasty 3d titles Sega ended up releasing on the 32x and the Saturn.

Courtesy of SMS Power! proof that Atari were penciling Sega title for release in 1995

Still, Atari pressed on regardless of that. An email from Atari operations John Skruch reveals that Atari and Sega managed to reach an agreement on their first five games — Outrunners (the questionable split-screen Megadrive version), Phantasy Star II, Alien Storm, Shinobi and Zaxxon 3d. A list of pending Jaguar titles produced later also suggests Atari had provisionally penciled Outrunners and Zaxxon for release for some point in 1995.

So why have you never seen anyone talking about Sega’s Atari Jaguar titles? As so often happens in history, fate intervened. By the 1990s, Atari was no longer run by Jack Tramiel but by his son, Sam. Sadly, as 1995 dawned and the Jaguar was approaching a truly make-or-break position, Sam Tramiel suffered from a health scare which forced him to step away from the company. Having retaken the reigns, Jack Tramiel didn’t have the same confidence in either the Jaguar console or in the video game market more generally that his son had. He opted to scale back Jaguar operations completely and in 1996 he arranged for Atari itself to merge itself out of existence with the hard-drive making JTS Corporation.

The nature of the merger highlights why you shouldn’t judge a console by the financials alone. By any measure the Jaguar can be said to be a failure: lifetime sales were probably no more than 300,000, its library of games was small and its’ only real gifts to posterity were an interesting Alien Vs Predator title and the template from which other console versions of Doom were spawned. Though a Jaguar 2 existed on paper and a small number of units of a CD add-on staggered into the market place, continuing the brand simply wasn’t a realistic option. Despite this colossal failure, however, Atari’s patent-chasing meant that the company was actually sitting on (but rapidly burning through) vast stacks of cash.

The merger was a marriage of convenience then: Atari were a financially successful company that risked running out of cash purely because they had no products to sell. JTS had hard drive products it could potentially sell but found itself with a bit of a cash flow problem. Simple. Not that the marriage would really help either party in the long run, mind you. Though Jack Trimiel secured a seat on the JTS board, more financial problems forced the sale of the Atari name to Hasbro in 1998 and JTS ceased trading a year later.

Yes, Sega really released Pong for the Megadrive in 1996

Consequently, the only product which emerged from the agreement between Sega and Atari is on the Sega side. For their part, Sega managed to release three Atari games though they did so in one collection. Sneaking onto the Megadrive and Game Gear in 1996, Arcade Classics is a really bizarre title if you don’t know the background behind. Farmed out to Al Baker and Associates, Arcade Classics was a port of three ancient Atari titles to Sega’s consoles, featuring the bare minimum in terms of options and upgrades. Worse still, these were of course ports of the home versions of these geriatric coin-ops — 7800 Centipede and 2600 Missile Command — rather than the arcade originals. Released a year into the life of the Sega Saturn and Sony PlayStation, Next Generation magazine unsurprisingly gave the Megadrive/Genesis collection a scathing single star rating. A fitting end to a cursed agreement:

Ultimately, those who unwittingly go searching for fond, nostalgic remembrances of their youth in Arcade Classics are more likely to discover suppressed memories of childhood traumas instead — Next Generation Magazine, September 1996.

So as the Atari/Sega rumpus shows, it probably shouldn’t come as a surprise if we still see companies using patents as a way to attack their competition today. From the moment the Atari Corporation launched their 7800 console, there was never really a point where the company looked like a serious contender in the video game console space. We can definitely question the morality of their use, there’s no denying that patents owned by the Atari Corporation kept the company afloat in the mid-nineties and almost scored them some prized software titles from the library of one of their main competitors. It’s unlikely, but were it not for Sam Tramiel’s health scare, they even stood a chance of turning the fate of the company around.

On Sega’s part, we can say from 1993 the dice frequently decided to fall against their favour. I wouldn’t say that their patent losses were the only reason they ended up crashing out of the console business in 2001, but by the end of the decade the company sorely missed the $90 million that the US arm had ended up paying to settle patent disputes. Whether we like it or not, the Atari/Sega case shows us that courtroom drama can shape the future of the games industry just as effectively as a hit game or console.ari’s library was more useful to Sega than Sega’s was for them. He might have actually had a point: aside from Atari’s legacy of classic arcade games (well, the ancient home ports of them at least), the early release of the Jaguar console meant that Sega would have had access to Jaguar titles like Tempest 2000 and Cybermorph before Atari had access to the tasty 3d titles Sega ended up releasing on the 32x and the Saturn.

Still, Atari pressed on regardless of that. An email from Atari operations John Skruch reveals that Atari and Sega managed to reach an agreement on their first five games — Outrunners (the questionable split-screen Megadrive version), Phantasy Star II, Alien Storm, Shinobi and Zaxxon 3d. A list of pending Jaguar titles produced later also suggests Atari had provisionally penciled Outrunners and Zaxxon for release for some point in 1995.

So why have you never seen anyone talking about Sega’s Atari Jaguar titles? As so often happens in history, fate intervened. By the 1990s, Atari was no longer run by Jack Tramiel but by his son, Sam. Sadly, as 1995 dawned and the Jaguar was approaching a truly make-or-break position, Sam Tramiel suffered from a health scare which forced him to step away from the company. Having retaken the reigns, Jack Tramiel didn’t have the same confidence in either the Jaguar console or in the video game market more generally that his son had. He opted to scale back Jaguar operations completely and in 1996 he arranged for Atari itself to merge itself out of existence with the hard-drive making JTS Corporation.

The nature of the merger highlights why you shouldn’t judge a console by the financials alone. By any measure the Jaguar can be said to be a failure: lifetime sales were probably no more than 300,000, its library of games was small and its’ only real gifts to posterity were an interesting Alien Vs Predator title and the template from which other console versions of Doom were spawned. Though a Jaguar 2 existed on paper and a small number of units of a CD add-on staggered into the market place, continuing the brand simply wasn’t a realistic option. Despite this colossal failure, however, Atari’s patent-chasing meant that the company was actually sitting on (but rapidly burning through) vast stacks of cash.

The merger was a marriage of convenience then: Atari were a financially successful company that risked running out of cash purely because they had no products to sell. JTS had hard drive products it could potentially sell but found itself with a bit of a cash flow problem. Simple. Not that the marriage would really help either party in the long run, mind you. Though Jack Trimiel secured a seat on the JTS board, more financial problems forced the sale of the Atari name to Hasbro in 1998 and JTS ceased trading a year later.

Consequently, the only product which emerged from the agreement between Sega and Atari is on the Sega side. For their part, Sega managed to release three Atari games though they did so in one collection. Sneaking onto the Megadrive and Game Gear in 1996, Arcade Classics is a really bizarre title if you don’t know the background behind. Farmed out to Al Baker and Associates, Arcade Classics was a port of three ancient Atari titles to Sega’s consoles, featuring the bare minimum in terms of options and upgrades. Worse still, these were of course ports of the home versions of these geriatric coin-ops — 7800 Centipede and 2600 Missile Command — rather than the arcade originals. Released a year into the life of the Sega Saturn and Sony PlayStation, Next Generation magazine unsurprisingly gave the Megadrive/Genesis collection a scathing single star rating. A fitting end to a cursed agreement:

Ultimately, those who unwittingly go searching for fond, nostalgic remembrances of their youth in Arcade Classics are more likely to discover suppressed memories of childhood traumas instead — Next Generation Magazine, September 1996.

So as the Atari/Sega rumpus shows, it probably shouldn’t come as a surprise if we still see companies using patents as a way to attack their competition today. From the moment the Atari Corporation launched their 7800 console, there was never really a point where the company looked like a serious contender in the video game console space. We can definitely question the morality of their use, there’s no denying that patents owned by the Atari Corporation kept the company afloat in the mid-nineties and almost scored them some prized software titles from the library of one of their main competitors. It’s unlikely, but were it not for Sam Tramiel’s health scare, they even stood a chance of turning the fate of the company around.

On Sega’s part, we can say from 1993 the dice frequently decided to fall against their favour. I wouldn’t say that their patent losses were the only reason they ended up crashing out of the console business in 2001, but by the end of the decade the company sorely missed the $90 million that the US arm had ended up paying to settle patent disputes. Whether we like it or not, the Atari/Sega case shows us that courtroom drama can shape the future of the games industry just as effectively as a hit game or console.